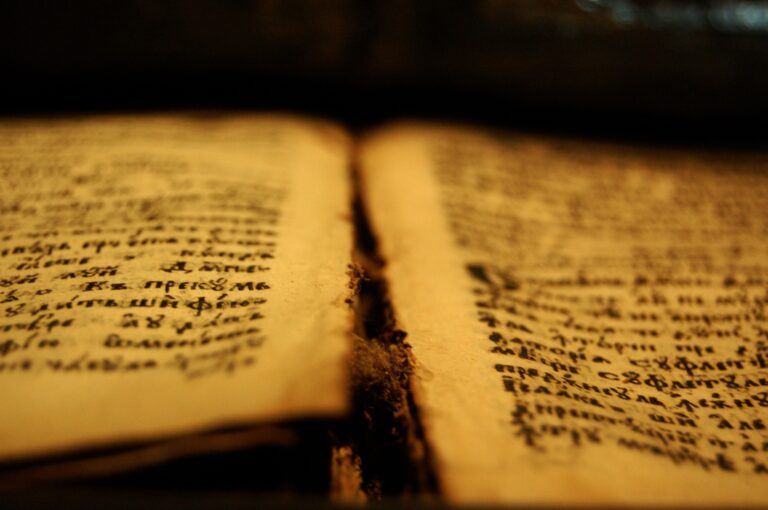

This is the fourth installment in my series on the Nicene Creed. You can read the first three installments here, if you are interested. This post will take a look at another one of the more interesting controversies surrounding the creed, involving, literally, one little letter. But that one little letter makes a world of difference.

I remember when I visited China several years ago sitting down at a restaurant with some of my Chinese friends. I was going to attempt to order my food and asked how to say the “tea” in Mandarin. They pronounced the word for me and then I repeated it. As I said the word several times to try and get it just right, some at the table began smiling. Apparently, if you don’t get the pitch just right, you can change the word entirely and it means something completely different, in this case, something that one does in the bedroom. I elected to have my friends order for me.

When the emperor convened the council at which the Nicene Creed would be written, one of the more salient points of debate was over a single letter. Was Christ homoousious with the Father or was he homoiousios?

Christians looked at the person and work of Jesus and they saw him doing the works of God (John 2:1-11; 5:1-9), taking the names of God (John 8:48-59), and receiving the worship of God (Matthew 28:9, 17; Luke 24:52; John 20:28). Of course this must mean he is God! Yet how do we reconcile these facts with the oneness of God taught in other passages like Deuteronomy 6:4? So, if Jesus is God and the Father is God, how exactly can there be one God? Jesus himself taught that He and the Father are one (John 10:30), yet Scripture clearly reveals them as somehow distinct (for example, we see Jesus praying to the Father in Luke 22:42 and the Father clearly speaking from heaven to the Son in Matthew 3:17 and other places). The early Christians wrestled with these passages and many others as they sought to understand the relationship of God the Father and Jesus. The two terms mentioned above, separated by only one letter, captured the positions of different camps as they struggled to describe this relationship from Scripture.

There once was a time when Christ was not

Before we can properly understand the significance of this one letter, we need to quickly review why the council was convened in the first place. As explained in one of my previous posts, one of the reasons the council was convened was because of the teaching of Arius, a popular leader and teacher in the area of Alexandria (Egypt) in the fourth century. One thing you have to understand about this time and place is that conversations about the Trinity were wildly popular, though often mired in complexity. Arius (256-336), thought that the relationship of the members of the Trinity could be explained in simpler terms. Influenced by the writings of another controversial figure from the same city, Origin, he began arguing that Jesus was a created being. As quoted in the other article:

“In the Fourth Century these discussions came to a head when Arius began arguing that Jesus was a created being. Arius, agreed with the general consensus at the time, that God is immutable, He doesn’t change. Change, as Arius and others reasoned, implies imperfection and God is perfect. If he changes, either for good or bad, he has either improved or regressed, which means that God cannot be absolutely perfect. The incarnation (Jesus, adding to Himself a human nature) suggested to Arius that God had somehow changed, which was an unacceptable way of thinking. Arius then reasoned that only God the Father was timeless (without beginning) and that the Son must have came into existence through the will of the Father. He argued that this all happened before Genesis 1:1 (before time began). In the words of Arius: ‘Before he was begotten or created or appointed or established, he did not exist; for he was not unbegotten.'” [1]

Two positions, two terms

At the council, the Arian position regarding the nature of Christ in relation to the Father, was that he was homoiousios, “of a similar substance” as the Father. Since Arius believed that Jesus was divine, he did not want to go as far as to say that Jesus was entirely different from God the Father (heteroousious). However, he did not want to say that Jesus was divine in the same way or to the same degree as the Father was. On Arius’ view, the Father had always been God, but not so with Jesus. Jesus “became” the God-man.[2]

The opposing viewpoint at the council, argued in favor of the term homoousios, “same substance.” Like homoiousios, this word is not found in Scripture, however, unlike the Arian term, it accurately conveys the Scriptural viewpoint of the deity of Christ, that Christ is of the same substance as the Father. The champion of this position was the bishop of Alexandria, a man named Alexander. He was deeply bothered by the teaching of Arius and began to speak out against it.[3]

The decision of the Council: Christ is of the same substance as the Father

Finally, the council, having weighed the arguments, landed on the side of Scripture and put the term homoousios in the Creed (technically, they used the term homoousion).[4]

An interesting side note about this controversy that the folks at Catholic Answers point out: “[N]otice that the difference between the spelling of the two concepts is the letter i, or iota in Greek. Some think that this is the origin of the expression ‘not one iota of difference’ as an expression of sameness.”[5]

[1] As quoted here: https://reddoorchurchofsoro.org/there-once-was-a-time-when-christ-was-not/

[2] Rick Gamble helpfully explains this point in his article at Ligonier “Not One Iota”: “At the incarnation, Jesus of Nazareth ‘became’ the God-man. Once again, on first reading, this phrase too is correct. Jesus did become the God-man two-thousand years ago when He was born of the virgin. But lurking behind this correct phrase was an overflowing garbage can of bad ideas. Any orthodox Christian today affirms that Jesus ‘became’ the God-man in the little town of Bethlehem, but we also affirm that the second person of the Trinity existed in full deity before that time. This pre-existence of Christ was the rub for Arius. He did not believe it, and he said, ‘there was a time when He was not [the eternal Son of God].’” See https://learn.ligonier.org/articles/not-one-iota.

[3] Later on, when Arianism took hold even after the council would go on to denounce it, Athanasius would rise up to defend the full deity of Christ. You can read an excellent article on the Life and Ministry of Athanasius here.

[4] The term homoousios is in the nominative (or lexical form), while homoousion is in the accusative form, as it is used in the sentence where it can be found in the Nicene Creed.

[5] See the article at: https://www.catholic.com/qa/one-iota-of-difference.